The Dunera Boys

Although born and educated in Australia and a valued dairy farmer in the Bega Valley on the Far South Coast of NSW my uncle Augustine Behl, a young man in his early thirties was detained at the beginning of World War 2 , as he was of German dissent. He was declared an alien in his own homeland . However not rounded up and imprisoned with hundreds of other men because he was essential for the food production line as a daily farmer. Rarely did he come into town . Tuesdays my aunt and two cousins came in for shopping and came to Nannas where we stayed in the Christmas holidays.

When he was in town, it was to sell and buy at the Sale Yards. However I am not sure if he was forbidden in town socially or if he chose not to come in. He was a very silent man and spoke few words to anyone.

It was at his property that I heard my first classical record and saw a record playing. It was Mario Lanser singing The Student Prince and I was blown away. His parents had brought the music from their homeland. and at the time it was the most beautiful thing I had ever heard. In a way I kept looking up, thinking it was coming from heaven.

Hence my interest in the story of the Dunera Boys a very interesting exhibition, curated by Louise Anemaat, Seumas Spark and andrew Trigg presently at the NSW State Library.

The Dunera Boys

They have become know as the Dunera Boys they sailed to Australia on the Dunera.

The story goes that when Winston Churchill came to power in Britain in May 1940, one of the first decisions of his government was to arrest, intern and ultimately deport thousands of ‘enemy aliens’ to Canada and Australia for fear that they might secretly help to orchestrate an invasion of Britain. On 10 July 1940, the British troop ship HMT Dunera departed Liverpool, Britain, with about 2120 male ‘enemy aliens’ on board. Many of the internees were Jewish and had fled to Britain as refugees from Hitler’s regime. Others had been there for years and had made their lives there. Though the Dunera internees did not know it when they left England, they were destined for Australia.

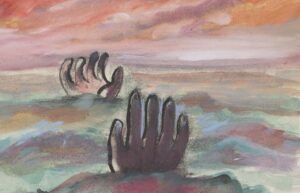

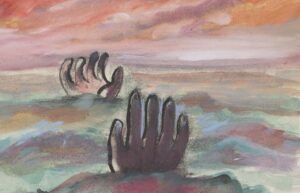

In powerful artworks, internees convey the experience of internment rather than the reality of its lived experience. In this artwork by Georg Teltscher, ghostly hands seem to be disappearing in an unsettled ocean, or rising up from a foaming landscape.

Conditions on the Dunera were dire.

The ship was grossly overcrowded,

men crammed into appalling quarters.

Toilets overflowed, poisoned the stale air.

British soldiers guarding the boys

treated their charges with brutality,

abusing them

stealing their possessions.

Throwing their bags overboard

The Dunera docked in Sydney

The internees, herded on to trains

ended in the remote, rural town of Hay.

In drought, everywhere was dry

flat and full of dust.

Relentless heat and swarms of flies

added to the internees’ sense of dislocation.

So unfamiliar was the landscape to European eyes

that many labelled the Hay plains a ‘desert’.

To try and make sense of the world

and their place in it they created friendships,

schools of learning ,

different classes were set up

they educated each other.

Drawing and art were lessons that endured

and is much of our evidence today.

Music played a big part .

The people of Hay rounded up musical instruments.

Today for us this is a reminder that coping

and surviving is about intellectual engagement

with place almost as much as it is about physical needs.

Art has long been an outlet to communicate when seeking to understand and give voice to what is not easily put into words. It reminds us that forced displacement is both a historic and a contemporary story, whether the result of war genocide, natural disaster, colonisation, whether on racial, ethic, political or religious grounds or increasingly because of climate change.