Hildegard of Bingen: Giving Women a Voice

A WOMAN’S VOICE ACROSS THE AGES

by Colleen Keating

(for the SWW Non-fiction writing)

by Colleen Keating

Trudging uphill, a small white butterfly crossed my path. I stopped. My eyes, following its

flirting curve upward, were caught by a rustic wooden sign with the word Klosterruine, the ruins of a monastery.

I walked with new purpose and new energy. Being mid-morning, the sun played on my back throwing a forward-onward shadow of joyful anticipation. Yet already it had the promise of a sweltering July day. As a pilgrim the map and compass were no longer needed. I felt close to my destination. All my concerns and sense of uncertainty lifted as lightly as the butterfly wings.

I had set out after breakfast from my hotel in the German town of Bingen on the Rhine River. With the language barrier I was unsure of my way. After two trains and about thirty kilometres inland via Bad Kreuznach I arrived at Staudernheim. Being a deserted and unmanned railroad stop didn’t help. However my mud map had my destination – Disibodenberg to the west. Thus began this uphill walk and into a dappled shady grove. With its lostness of ruins I found myself in a world of another time.

I had come in search of a woman known as Hildegard of Bingen. Well actually I had come in search of the ancient ruins of an abbey, where she had lived for forty-four years from the age of eight. And now this is where I stood, feeling an overwhelming presence.

As a woman from Australia this was a dream come true. Hildegard has been my inspiration as a woman, wife and mother, a healer, environmentalist and writer since I first came to know her.

Hildegard lived in the 12th Century, in the rich Rhineland Valley in Germany, a writer, composer, artist, naturalist, healer, leader and most importantly a prophet for her time. Today we call her a mystic. She stood up and was listened to by popes and leaders. She spoke from her own feminine power, her own feminine centre. And her voice was backed by practical application. Today her medieval wisdom, that spoke always from a feminine truth and perspective, gives us renewed hope. Renewed hope, as we struggle with the issues of caring for our earth, caring for our body, sustainability, climate stress and human relations; inequality and injustice, especially towards women; corrupting power in religious and secular institutions and corporations. For us today her voice is a rainbow bridge spanning nine centuries, with its many strands.

But gradually her voice fell silent.

Now after nine hundred years she has been rediscovered . For us, as women of the 21st century her voice speaks out ‘purely’. I say purely, for Hildegard’s words and music are from before the Dark Ages, before the stranglehold of the patriarchal church, before the burning of the sages and healers as witches, before the banning of books. Hildegard believed in women empowering themselves and finding a distinctively feminine voice. A voice, unlike male writing that transcended the body to find its spirituality, Hildegard’s voice is embodied in the earth, health, food and fertility.

The first time I heard of Hildegard was when I came across her mandalas in a friend’s book, around 25 years ago. They took my breath away. Her mandalas are minutely detailed circular drawings representing the universe and its oneness. They reminded me of the first time I saw the photo of our fragile blue planet floating in space, taken by the crew on Apollo 8 in 1968. Her drawings have a mystical quality and a ‘knowing’ that is prophetic. With one of her cosmic mandalas she wrote:

“The earth is at the same time mother, she is mother of all that is natural, mother of all that is human. She is the mother of all, for contained in her are the seeds of all.” 1

Her biographer states: “Hildegard reminds women of the power of their prophetic voice, and not to be afraid to stand up to power over issues that truly matter, such as the way we are treating Mother Earth and the way power corrupts – including religious power. And to put the God of Life ahead of the God of Religion as circumstances dictate.” 2

The twelfth century gave birth to a Renaissance. Hildegard of Bingen whose lifetime spanned eighty percent of that century (1098-1179) stood out as a woman of extraordinary spirit and courage. In her life time Chartres Cathedral rose from the grain fields of France with its delicate stain glass and inimitable sculptures. Frederick Barbarossa was the powerful Emperor of the Holy

Roman Empire. The second violent Crusade was launched and the University of Paris was evolving. There are letters of Hildegard admonishing these leaders and replies to show she was listened to.

Hildegard was the last of ten children. She was an unusual child and a day-dreamer. Her ageing parents placed her under the tutelage of Jutta von Sponheim – “as a gift to God.”

This idea of the ‘tithe’ of a child to the Church was not uncommon. And so at the age of eight years old Hildegard came to live on the outskirts of a Benedictine monastery of monks, under the tutelage of the older hermit Jutta. This monastery was set up in the hills behind Bingen at Disibodenberg. And now I was here.

My every step was absorbed by soft verdant grass and I was alone in utter wonder. At first it was like entering a secret garden. This over grown shady grove unfolded like a history book. Stone patinated with moss and algae, crumbled columns, stairs down to nowhere, rocks scattered half- buried by vines and gnarled tree roots like pythons gnawing the earth, strangling and moulding their abode. Today it is a protected site and tranquil like a pre-loved garden. I followed the worn path to the outskirts of the walls and here I found a small plaque Hildegard Kapelle (meaning her cell or chapel). A rambling red rose in full summer bloom grew across the broken stone wall. I found a place to sit. Delicate maidenhair ferns grooved into a cool crumbling niche. My heart was on fire.

This is where by osmosis Hildegard absorbed the songs and prayers and stories of the Bible. Jutta schooled her in the ways of monastic life. There would have been many happy and often sad and lonely times for this young girl. This is where Hildegard lived for forty-four years. A time she later called her kairos time. Besides gardening, weaving, spinning and learning the psaltery (a zither-like string instrument) and the chores of her life of service, Hildegard was becoming very learned in the nutritional value of herbs and the making of tonics and salves.

Hildegard learned quickly and intuited much. As the years went by many women began coming to her and Jutta for counsel with women’s health and medical issues. They benefited from their advice and the herbs, salves and tonics they made.

Even though this hermitage was a crammed space Hildegard’s charisma spread, and a number of young girls came to join them. They became a small parallel convent under the Benedictine Rule confined to a space still outside the monk’s Monastery.

Hildegard had heard ‘voices’ from when a young girl. For many years she suppressed this and she often felt a malaise (now thought to have been migraine). As time went on she felt a powerful call to write. It took her over two years to build up the courage to approach Abbott Kuno and another two years to get his permission. She was given a secretary, a former teacher called Volmar, to be her scribe.

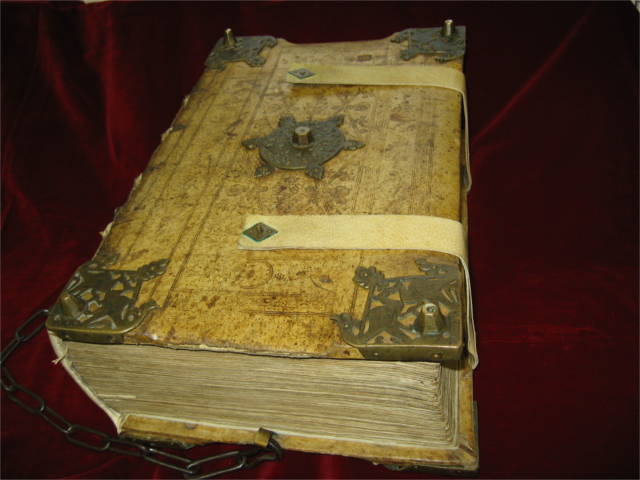

And so at the age of forty-two years and 7 months, the writing down of her visions began. As her creativity increased her malaise lifted. The first of her nine books called Scivias ‘Know the Way’ took ten years to write and contained 26 visions with drawings and detailed mandalas of great beauty. Her famous Causae et Curae discusses the symptoms, causes and cures of physical ailments, all very much based on finding balance internally and externally. She reveals an understanding of the whole human being and sets forth a comprehensive system of healing – mind, body and spirit. Her way is truly holistic. Over the next forty years she wrote texts on theology, on creation, the environment, on medicinal herbs and teas, on botanical and biological observation including herbal advice. Her writings became well known throughout Europe and as far as Rome. In many of her letters she advised political leaders, and into her late seventies she went on preaching tours. She has left us with over one hundred letters, seventy poems, a play as well as the nine books.

Not long after Jutta died in 1136, Hildegard had a vision for her sisters and found the courage to act. She decided to build a Benedictine Abbey for women. The Monks refused to allow the move. They enjoyed the revenue that the women brought in by their hard work. In spite of being a woman in a male-dominated period with no formal education, Hildegard found her power. Hildegard stood up to the men and finally won, after taking to her bed and refusing to work.

Hildegard acquired land for her first Abbey in a strategic place at the junction of the Nahr and Rhine Rivers, just north of Bingen at Rupertsberg. She oversaw its construction. Hildegard saw to it that the plan included plumbing with running water and sanitary standards unknown for her women before this. They cultivated a vineyard and bottled wine. Hildegard believed wine was a medicine for warmth and well being, especially at times of women’s menstrual cycle.

Hildegard and her sisters had a garden which provided many nutritional and medicinal needs for the infirmary that she set up. People of the district, and further afield, streamed to the Abbey for her holistic advice and medicinal help.

For the next forty years she ran a vibrant Abbey. As the number of women increased she decided to expand and build a second Abbey. At the age of sixty seven, which was quite old for her time, Hildegard chose a wonderful position high on the hill on the opposite side of the Rhine River at Eibingen. She also planned and oversaw the construction of this second Abbey.

On my pilgrimage it was exciting to search out the two Abbeys she built. The first one at Rupertsberg is difficult to find. Today it is in a busy business section of the town of Bingen and has only a small sign out the front which could easily be missed.

All these centuries later nothing appears left of this once vibrant community of buildings and gardens, said at one stage to include 300 women. It was burned to the ground during war with Sweden in 1632 and the French destroyed the last remains in 1689. However, though it was destroyed and forgotten, it was rediscovered when they surveyed for the railway line that now runs through the area. There were already buildings on top but they excavated and the layout of this ancient Abbey was discovered.

I was met by a Benedictine nun who excitedly took me down into a few re-created rooms. Our meeting and the rapport we developed was one of my most touching experiences and a highlight of my pilgrimage. She spoke vibrant, energetic German explaining it all to me and I just said “yah” and nodded and smiled and looked at all in wonderment. Then I would say something in English and she excitedly told me more in German. We couldn’t understand each other but our spirits were one and our hearts understood every word. We stood together in the room where Hildegard died. It was a poignant moment. She spoke passionately and was happy to have someone to whom to tell the story. The sisters have re-created the space with murals, as to how they believe it would have been. And I felt humbled and overwhelmed with happiness to be there.

My next step was to take the ferry across the Rhine. I walked up the hill to the second Abbey which has been rebuilt in the last four hundred years and is still a working concern with forty sisters who live the Benedictine life. This was a time to experience the charisms of Hildegard’s legacy.

I planned to stay a few days and enjoy their hospitality. I fell easily into the Benedictine rhythm of

the ‘contemplative in the world’ being in the moment, aware of the call of the dawn, waiting upon the day, listening to the dusk, letting go of the dark and listening to the landscape around me. There was a spaciousness in my days, with ruhr (silence) always welcome. I enjoyed the bells calling to prayer with chanting and singing. I enjoyed spelt bread and wine from Hildegard’s recipes and teas and I found her spirit alive in the joy of the sisters.

Behind the Bingen Museum I discovered a garden which is dedicated to Hildegard. Many of the herbs and plants that Hildegard mentions in her writings are growing there. Hildegard saw health as “moist, wet, juicy as the succulent fruit on the vine”.

She would counsel:

“do not allow yourself to be drained dry”3

She coined the word ‘viriditas’ to describe the greening power, the moistness and quenching of thirst that wisdom herself promises. She used ‘viriditas’ to describe the divine vitality that fills the world.

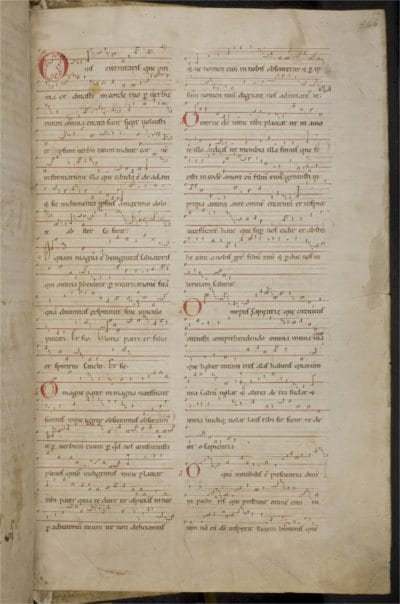

Today more people are aware of Hildegard through her music than any other of her endeavours.

She composed music for her sisters to sing. She was aware of the power of music to lift their spirits, and it gave a joyful and celebratory feel to every day. Her morality play and the dressing up and laughter and fun were part of this.

Her words are valuable mantras for us:

“Be not lax in celebrating.

Be not lazy in the festive service of creation.

Be ablaze with enthusiasm.

Let us be alive” 4

Even though her music was lost to the world for 900 years, Hildegard ’s music was waiting to sing for our earth again.

“For Hildegard there is no truer, deeper or more cosmic way to celebrate ‘being’ than to make music, for all of creation is to her a symphony”. 5

Today it is revived by many ancient music specialist groups all over the world and still lifts spirits Her music is very popular on ABC FM and was in the top 100 survey of loved music in 2014.

Heather Lee, a singer and scholar of ancient music says of Hildegard’s music:

“It’s a fantastic experience to sing her work, because it just puts you in her consciousness in the 12th Century, you know, you’re there through her style of music. For her time, it was quite innovative because she was singing higher notes than anyone else. She went up to a top G. That was never done before, and it’s technically beautiful to sing, it’s soaring, it’s flowing and it’s all on the breath. “ 6

For me, Spiritus Sanctus from the CD Canticles of Ecstasy is one of the most beautiful compositions. Hildegard sings of the Holy Spirit moving through the body and so the breath moves. The breath – that was everything to her. Spirit flowing through the body and the mind and that was what she lived for and what she gave to the women that gathered around her. And for those that listen she gives it still today.

Hildegard gave the earth a voice. Her message was to care for the earth as you would care for your mother. In her prophetic way she saw all of life as interconnected. She reminds us to remember who we are, not set apart and superior, not meant to dominate this world, but with the honour to receive abundantly as the trusted stewards of the earth.

In my essay I hope I have given the reader a taste of Hildegard’s message, and the sound of her voice. Most importantly, Hildegard was a woman who spoke out.

“From the pain and darkness of her own journey she spoke out. And she sang out and wrote out. And travelled out. And preached out” . 7

She challenges us as women to reclaim and be the healing feminine voice for our time.

Now after two pilgrimages to Germany, I am still journeying to discover and enjoy the spirit of this amazing woman. Oh the sheer delight of hearing this lost woman’s voice from 900 years ago, speak for women today in the 21st century.

May her genius come alive for you and now having read these few words may you too go on to discover her for the rest of your life.

7.

FOOT NOTES and REFERENCES

1 Hildegard of Bingen , Scivias, trans. by Mother Columba Hart Paulist Press NY 1990

2 Fox, Matthew, Original Blessing Bear & Co NM 1983

3. Fox, Matthew, Illuminations of Hildegard of Bingen, Bear & Co 1985

4. A Feather on the Breath of God Sequence and Hymns by Hildegard of Bingen

Hyperion 1982

5 Fierro, Nancy, Hildegard’s Music.org/music

6 Heather Lee .Winner of the Australian National Aria Award and Scholar of Sacred Music

Rhythm Divine ABC 2011. Her CD Sacred Fire: Music of Hildegard von Bingen

7 Matthew Fox 1985 Ibid pg. 18

A VALUABLE REFERNCE

Hildegard of Bingen’s Medicine by Dr. W. Strehlow & Dr. G Hertzka. Bear & Co 1988

8.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Today being Hildegard’s Anniversary of her death in 1179 and having just finished a VIRTUAL PILGRIMAGE with group of Hildegardians I thought this blog Healthy Hildegard sums up 20 reasons why so many turn to Hildegard today in this 2020 year. I hope my following this link you will be blown away with the detail

Thank you to the wonderful blog Healthy Hildegard

https://www.healthyhildegard.com/hildegard-von-bingen/

Since 2014, we’ve been working on compiling information about Hildegard von Bingen and her remarkable life. Our initial motivation came from a genuine interest in Hildegard’s midlife awakening. Most of all, the notion that a purpose-driven life can begin at 40 — and if we listen to our inner voice and spirit, we will find our purpose. Over the years we’ve discovered that Saint Hildegard of Bingen offers much more than just inspiration.

Hildegard von Bingen’s Remarkable Contributions

Hildegard has long been recognized as a meaningful religious and historical figure. But it wasn’t until 2012 that her contributions to spirituality and medicine resulted in her canonization as a Saint and doctor of the Church.

Through our exploration of Hildegard von Bingen’s life and accomplishments we’ve discovered and documented many remarkable things we didn’t know about Hildegard. So we decided to categorize many of them and share them with you here as the 20 things you may not know about Hildegard von Bingen.

20 Remarkable Things You May Not Know about Hildegard von Bingen

1. Hildegard was one of the most important composers of the Medieval Period.

Hildegard von Bingen considered music to be the point where heaven and earth meet. So it is no surprise that she believed harmony to be more than the combination of voices and instruments, for Hildegard, music represented the balance of body and soul. She saw music as the interconnectivity between man and the universe.

There is much more to know about Hildegard as a composer and Hildegard’s music. We have compiled a comprehensive introduction to Hildegard of Bingen’s music with help from a foremost expert on Hildegard’s music, Dr. Barbara Stuehlmeyer.

2. Hildegard von Bingen’s writings were visionary and ahead of her time.

Hildegard von Bingen made a remarkable historical impact. As a result of her unique thinking and diligence in recording her work, her contributions survive to this day. Hildegard’s work touches on virtually every part of our human beliefs and practices, covering centuries of human experience. Hildegard of Bingens’s prodigious contributions result from her vast output and vigorous dedication to work.

In Hildegard’s first and perhaps most famous theological work, Scivias she documents her visions and prophecies. Her subsequent tomes, Physica and Causae et Curae memorialize her healing methods.

Her Book of Life’s Merits contains one of the earliest descriptions of Purgatory. See our assembled list of the most prominent Hildegard of Bingen’s writings.

3. Hildegard von Bingen’s medicine remains prominent in Germany today.

Hildegard of Bingen’s background in healing was as a function of her duties as a nun (and eventual Abbess). Hildegard of Bingen’s medicine, and the medicine of her time, was practiced within the confines of the monastic community.

Today, this practice is known as monastic medicine, or klosterheilkunde in German. In recent years, monastic medicine has gained recognition within the scientific and medical communities. Like most medieval medical treatments, Hildegard of Bingen’s natural healing techniques were rooted first in the principles of scripture and the Order of St. Benedict.

4. Hildegard’s emphasis on grains may not have been focused on spelt.

Many consider an inseparable relationship between Hildegard von Bingen and spelt. Despite popular contemporary thinking around Hildegard and spelt, Hildegard’s writings do not focus on specific spelt recipes. Instead, her work notes the general attributes and benefits of spelt as a healthy plant.

In Physica, and perhaps other soundbites on spelt that we’ve collected, Hildegard von Bingen recognizes the value of spelt as a perfect grain. She reserves most of her favorable commentary for wheat and rye. Given how much grains have changed over the last 900 years, perhaps Drs Hertzka and Strehlow were right to propose the use of ancient dinkel grain for the gluten effects in spelt and for overall intestinal health.

5. Hildegard von Bingen’s mysticism promotes a oneness with nature.

Hildegard von Bingen’s spirituality has roots in the doctrine and theology of the Catholic Church. She was canonized as a Saint and recognized as a Doctor of the Church in 2012 as a result of her contributions to theology and medicine. Most noteworthy is that Hildegard is one of only 36 people (and only 4 women) to be named Doctor, during the entire history of the Church.

Hildegard von Bingen is also recognized as a visionary and a mystic. Her mysticism is widely appreciated and celebrated. So much so that Michael Conti named his movie Hildegard, The Unruly Mystic. Matthew Fox’s Fox Institute for Creation Spirituality also dedicates a portion of its curriculum to the study of Hildegard’s mysticism and her appreciation of nature. Furthermore, Terry Degler wrote a wonderful piece illustrating how Hildegard von Bingen’s spiritual awakening is like that of a Kundalini awakening process.

6. Hildegard documented the midlife awakening that inspired Carl Jung.

Our relationship with Hildegard von Bingen started by learning of her personal spiritual evolution. We call her midlife transition since she came into her purpose at midlife. We also discovered that Hildegard of Bingen was transformational, embracing a new life and spiritual path in her early forties. Her awakening would result in the most prolific and creative period of her life — with her life continuing into her early eighties.

We consider Hildegard’s midlife awakening among her most valuable contributions. It reminds us that we have the power to change these lives we’ve led and to find our bliss. Carl Jung also found inspiration in Hildegard. As a result, he referenced Hildegard of Bingen in his research on the individuation process. Avis Clendenen meticulously documented Jung and Hildegard in her book, Experiencing Hildegard.

7. Hildegard von Bingen inspires to us embrace our gifts despite potential risk.

Even a biography of Hildegard von Bingen is an inspiring body of work. Through the process of learning about her life, we have discovered that Hildegard von Bingen was transformational. Hildegard demonstrated a new way of thinking and living during a time when little was expected of women, particularly within the confines of a church governed through patriarchal rule.

Today, Hildegard of Bingen is a Saint and one of a handful of Doctors of the Church. Critics have pointed to parts of Hildegard’s generally accepted biography as overly romantic to satisfy hagiography. Even without consideration for whether she was in fact tithed to the Church as a child or if she served in seclusion as an anchorite, the lasting effect of Hildegard of Bingen’s many works and writings speak to her tremendous influence.

8. Hildegard von Bingen’s medieval garden reflects a healthy body.

Dr. Victoria Sweet marvels at Hildegard von Bingen’s view of all aspects in nature as elements of a garden. Throughout her work, Hildegard emphasized the greenness of things, specifically the viriditas and healing of elements in harmony. We have Hildegard von Bingen to thank for discovering many of the healing plants to include in a proper Hildegarden and how her teachings can be the model for a successful medieval garden.

9. Hildegard von Bingen proposed basic nutrition in a medieval diet popular today.

At its core, the basic premise of Hildegard of Bingen’s healing harmony derives from balance and prevention. Hildegard would have us believe that we maintain health by enforcing some personal discipline and routine on matters such as diet, see cold weather foods.

Hildegard von Bingen advocated for a basic nutritional treatment founded in ancient traditions like breaking bread. Today, we can benefit from the same principals found in a medieval diet inspired by Hildegard. In addition, the modern slow food movement is much like how Hildegard saw food as medicine and how to take a walk after dinner for good health.

Since most of Hildegard of Bingen’s wisdom ultimately relied on common sense and moderation, we can adopt many of her practices rather easily. But there is still much more to her wisdom and work in natural medicine to be discovered.

10. Hildegard’s Viriditas reflects the power of nature in each of us.

Among Hildegard’s most recognizable contributions is her theory of Viriditas. Hildegard of Bingen believed that viriditas was what encapsulated the divine feminine force and the greening power of nature. As one might find in observing plant life, Hildegard of Bingen believed the unifying power of the divine shows itself in the form of growth.

In addition to physical health found through viriditas, we can also achieve mindfulness through viriditas. Like a form of dynamic meditation, we commune through our interconnectivity with nature. Dr. Nancy Fiero, a noted pianist and author of the book Hildegard of Bingen and her Vision of the Feminine wrote a poem she calls the Viriditas Prayer.

11. Hildegard’s fasting was a prescription for living in moderation.

Hildegard von Bingen is known in Germany as the founder of alternative medicine and for her contributions to holistic health and wellness. Those devoted to Hildegard nutrition often commit to some form of periodic fasting regime. Much like the affiliation of spelt to Hildegard, there is some dispute about Hildegard of Bingen’s’s actual endorsement of fasting, however there is little dispute over the importance of intestinal health in Hildegard medicine.

We believe fasting corresponds closely to Hildegard’s belief in routine, discipline, and discretio. Hildegard of Bingen’s guide to fasting and health advocates for moderate fasting guidelines to renew and preserve good health. In Germany, Hildegard von Bingen is known for three discrete healthy fasts, whereas in the US, Hildegard’s regimen is normally considered a spiritual fast from antiquity.

12. Hildegard of Bingen closely observed and documented human ailments and remedies.

As implied by our name, Healthy Hildegard is largely dedicated to recognizing ailments documented by Hildegard, and finding suitable Hildegard-inspired remedies. For easy reference, we’ve aggregated Hildegard of Bingen’s 11 best natural remedies.

There are several well-known treatments, within the context of Hildegard’s cures, such as the Wormwood cure, Parsley wine, holistic allergy remedies, 3 natural cold remedies and the Duckweed elixir. Ultimately, Hildegard von Bingen believed our health depends on nature and our environment, so her remedies often align with seasonal changes. Consider herbal cold remedies in winter, the autumn Duckweed drink, the Spring Cleanse and even the Spring Soul Cleanse.

13. Hildegard von Bingen’s Ordo Virtutum was the first morality play and opera.

Hildegard von Bingen’s Ordo Virtutum deserves its own special category apart from Hildegard’s writings, broadly. In addition to Scivias, Ordo Virtutum represents Hildegard of Bingen’s acceptance of her own voice and visions, marking the point of her midlife awakening. See our translation text of Ordo Virtutum to read the voice of Anima tell the story of our soul, along with the guiding support of our subconscious virtues. In the original performance of Ordo, Hildegard played the queen of all virtues, Humility. We have had the pleasure of watching modern performances of Ordo Virtutum, including the San Francisco Renaissance Voices, and Tim Slover’s Pulitzer prize nominated play, Virtue.

14. Commission E has adopted many of Hildegard’s healing herbs.

Hildegard of Bingen’s medicine is based on the concept of finding our cues in nature. Whether through the divine healing power of viriditas, or our meditations in nature, the natural world provides the remedies for our lives.

Healthy Hildegard is largely based on rediscovering the healing herbs that Hildegard von Bingen described in Physica and Causae et Curae. Accordingly, we have attempted to distill some of the more complex findings that continue to persevere in klosterheilkunde, including Hildegard’s 7 healing plants, herbal high blood pressure home remedies, and Hildegard’s 9 herbs for painful menses.

For practical purposes, we also include 6 ways to preserve fresh herbs. Like Hildegard, we hope to achieve improved healing harmony and holistic health and wellness through plants and herbs.

15. Hildegard’s healing spices help incorporate natural herbs in our daily routine.

As with healing herbs, Hildegard of Bingen’s healing spices are a way to incorporate Hildegard nutritional therapy into our daily lives. Among the most important of Hildegard’s 13 healing spices we’ve found compelling reference to Bertram or pellitory, galangal (often confused with ginger), and Thyme benefits. Hildegard’s guide to fasting and health encourages the use of these herbs to preserve and maintain energy levels. Finally, Hildegard would also likely advocate for the use of one of these 24 bitter spices, which were mainstays of monastic medicine in her time.

16. Hildegard’s belief in interconnectivity underscores our balance with nature.

When we think about interconnectivity we think of being a part of something larger than ourselves. We seek to embraced the joy of giving to a greater collective purpose. Hildegard of Bingen envisioned this as a cosmic womb of the divine feminine.

Hildegard von Bingen’s Scivias formalized her view by proposing a model of the universe resembling an egg. She wrote of the microcosm and the macrocosm as a means to exemplify the spiritual and physical interconnectivity of man and the universe. Fittingly, through Hildegard’s work, we’ve come to understand that the easiest way to achieve interconnectivity comes through our relationship with nature. Thus we think Hildegard would approve of finding mindful meditation in God’s cathedral of nature.

17. Hildegard von Bingen’s creativity represents both an expression and form of prayer.

Hildegard von Bingen’s beliefs in the power of creativity comfort us by reminding us that life’s greatest forces are found in our ever-expanding universe of creativity. When we explore the outer limits of our creative power we bring to life the divine feminine within each of us. According to Hildegard, life’s greening force results from the creative power of viriditas.

These core beliefs contribute to Hildegard’s legacy as the Patron Saint of Creativity. We think of Hildegard having first revealed her creative power in her performance of Ordo Virtutum. This milestone event, as Teri Degler puts it in her piece describing Hildegard as a kundalini, represents a meaningful point of overcoming fear and personal risk to embark on a spiritual transformation.

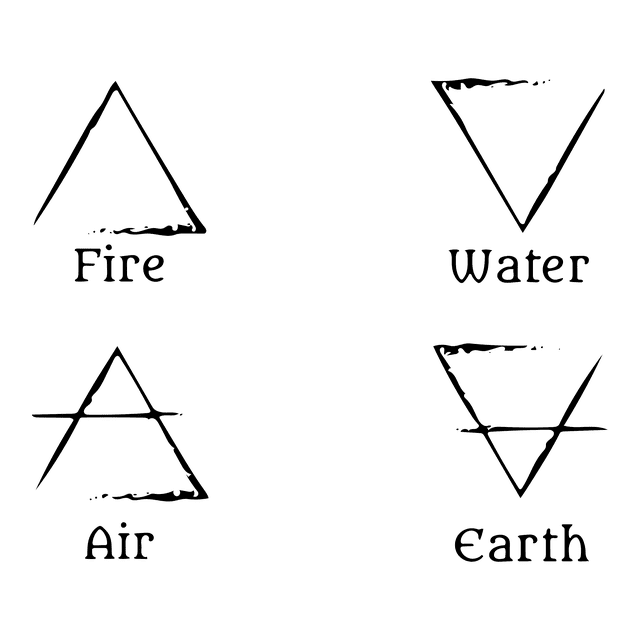

18. Hildegard’s of Bingen 4 bodily juices corresponds with seasons, directions and elements.

There has been much written about Hildegard of Bingen’s (and her predecessor’s) belief in humorism and humoral medicine. Though a believer in this ancient form of treatment, Hildegard had a rather small twist insofar as she viewed the bodily humors as four bodily juices.

According to Hildegard, four primary elements compose the Earth and the Earth was a gift to man from God. In her book, Rooted in the Earth, Rooted in the Sky, Dr. Victoria Sweet discusses the 4 elements as earth, fire, air, and water. Hildegard believed we find balance among the four elements. Accordingly, Hildegard believed that Fire strengthens, Earth provides life force, Air supports flexibility, and Water moisturizes and nourishes.

19. Hildegard von Bingen’s Discretio at the core of our mandate to manage our own condition.

Hildegard von Bingen’s concept of discretio is consistent with our understanding of discretion. So we refer back to discretio for various reasons throughout this site. From our Comments on a Hildegard Fast to Hildegard’s nutritional treatment, to Vindication for Breaking Bread, and of course Hildegard of Bingen medicine, discretion plays an important part in how we manage the routine of our daily lives.

It is particularly noteworthy that as far back as the middle ages Hildegard places much of the onus and responsibility of a healthy and productive life on our ability to manage ourselves.

20. Hildegard of Bingen liked bitter flavors to balance appetite and promote digestion.

Hildegard of Bingen’s concepts behind bitter tasting foods and bitters closely resembles the theory of bodily humors and elements. Accordingly, we experience five unique flavor profiles: sweetness, sourness, saltiness, bitterness, and umami (savory).

As a result of our tendency to avoid bitterness, our nutrition – and ultimately our health, suffers. Our western diet internationally avoids bitter flavors and foods in favor of more appealing flavors. Knowing what foods are bitter and how to incorporate those into our diet can greatly improve our intestinal health, reduce excessive appetite, and encourage a more diverse and nutritious bounty of foods into our diets.

Here are 17 bitter foods that you can learn about and start enjoying today.